A BIAS FOR ACTION

SETS GROWTH LEADERS APART

The world keeps getting more complex. We all feel this every day. Myriad disruptions arise, feed off one another, cascade around the world at an accelerated pace, upend our operations, and knock strategies off course. The leadership challenge is unprecedented: Amid so many formidable issues but daunting long-term disruptions and difficult short-term demands—how should we focus our all-too-finite resources of capital and time?

In our 4th annual AlixPartners Disruption Index, business leaders cite this as the central dilemma, with 85% of CEOs telling us that it has become increasingly difficult to know what to prioritize.

For more than 40 years, AlixPartners has been helping our clients navigate disruption. In an environment of relentless change, the lessons we have learned from our roots in turnaround and restructuring are as relevant for healthy companies as they are for troubled ones. One of the most critical lessons we have learned is that you cannot combat disruption if you are overwhelmed with distractions. You must cut through the noise to find and focus on what really matters. You must be willing to take bold actions to move your company where it needs to go. And to do so at speed.

Our survey identified a segment of companies we call growth leaders—enterprises that are outpacing their competitors. If one thing sets them apart, it is bold action. More than half are changing their business models this year. Across the board, we see them performing better, yet still trying to do more, whether that’s fixing their supply chain or attracting the best talent or transforming their business with technology.

And despite all the challenges, including any potential unknowns, growth leaders are optimistic about the future. New technologies promise to solve some of our most existential threats, including those arising from climate change and aging populations. Growing geopolitical competition and conflict could actually demonstrate the need for greater international cooperation. Disruption may be the new economic driver, but it creates opportunities, not just threats.

Leaders must be prepared to meet the challenge of this disruptive age. I hope this report provides some insight into how to do just that.

All best,

The world keeps getting more complex. We all feel this every day. Myriad disruptions arise, feed off one another, cascade around the world at an accelerated pace, upend our operations, and knock strategies off course. The leadership challenge is unprecedented: Amid so many formidable issues but daunting long-term disruptions and difficult short-term demands—how should we focus our all-too-finite resources of capital and time?

In our 4th annual AlixPartners Disruption Index, business leaders cite this as the central dilemma, with

For more than 40 years, AlixPartners has been helping our clients navigate disruption. In an environment of relentless change, the lessons we have learned from our roots in turnaround and restructuring are as relevant for healthy companies as they are for troubled ones. One of the most critical lessons we have learned is that you cannot combat disruption if you are overwhelmed with distractions. You must cut through the noise to find and focus on what really matters. You must be willing to take bold actions to move your company where it needs to go. And to do so at speed.

Our survey identified a segment of companies we call growth leaders—enterprises that are outpacing their competitors. If one thing sets them apart, it is bold action. More than half are changing their business models this year. Across the board, we see them performing better, yet still trying to do more, whether that’s fixing their supply chain or attracting the best talent or transforming their business with technology.

And despite all the challenges, including any potential unknowns, growth leaders are optimistic about the future. New technologies promise to solve some of our most existential threats, including those arising from climate change and aging populations. Growing geopolitical competition and conflict could actually demonstrate the need for greater international cooperation. Disruption may be the new economic driver, but it creates opportunities, not just threats.

Leaders must be prepared to meet the challenge of this disruptive age. I hope this report provides some insight into how to do just that.

All best,

In this, the 4th annual AlixPartners Disruption Index, we delve deeper into the changing nature of the global economy and what business leaders must do to adapt to and take advantage of these shifts. One thing is clear: Those leaders who say they are driving change in the face of disruption are behaving differently.

In this, the 4th annual AlixPartners Disruption Index, we delve deeper into the changing nature of the global economy and what business leaders must do to adapt to and take advantage of these shifts. One thing is clear: Those leaders who say they are driving change in the face of disruption are behaving differently.

We are in an era where the best-built plans of business are waylaid by forces beyond their control. A supply chain crisis. Hyperfast technological change. A pandemic. Climate change that alters industries and spawns more and more natural disasters. A sudden surge in inflation. A revolution in how work gets done—and in what employees expect. A war.

That’s why we say disruption is the new economic driver. Because every company, every executive team, every CEO must contend not only with the challenges of competitors, costs, and customers, but also with sudden shifts in the business environment and with inexorable, long-term trends that are transforming how businesses win—and lose.

As CEOs look at this disrupted landscape, the data show that they see opportunity and threat in equal amounts. Can they seize the opportunities and defeat the threats?

In the pages ahead, we present the findings of the 4th annual AlixPartners Disruption Index, based on a survey of 3,000 senior executives around the world. We delve deeper into the changing nature of the global economy and what business leaders must do to adapt to and take advantage of these shifts. We will also look at the unique behavior of the companies that are thriving—the one company in five that says it is leading the pack when it comes to growth in their industry.

We are in an era where the best-built plans of business are waylaid by forces beyond their control. A supply chain crisis. Hyperfast technological change. A pandemic. Climate change that alters industries and spawns more and more natural disasters. A sudden surge in inflation. A revolution in how work gets done—and in what employees expect. A war.

That’s why we say disruption is the new economic driver. Because every company, every executive team, every CEO must contend not only with the challenges of competitors, costs, and customers, but also with sudden shifts in the business environment and with inexorable, long-term trends that are transforming how businesses win—and lose.

As CEOs look at this disrupted landscape, the data show that they see opportunity and threat in equal amounts. Can they seize the opportunities and defeat the threats?

In the pages ahead, we present the findings of the 4th annual AlixPartners Disruption Index, based on a survey of 3,000 senior executives around the world. We delve deeper into the changing nature of the global economy and what business leaders must do to adapt to and take advantage of these shifts. We will also look at the unique behavior of the companies that are thriving—the one company in five that says it is leading the pack when it comes to growth in their industry.

Executives are struggling with shorter-term crises that demand their immediate attention, while longer-term structural changes are remaking industries and creating new winners and losers.

Executives are struggling with shorter-term crises that demand their immediate attention, while longer-term structural changes are remaking industries and creating new winners and losers.

Responding to disruption is the greatest strategic challenge for business

leaders, and it is unlike the tests they are used to. They must confront an environment that is shaped not just by the magnitude and sheer number of different disruptive forces, but also by their unpredictability and the complexity of their interconnected impact.

The AlixPartners Disruption Index—a measure of the number and intensity of disruptive forces companies face—edged down this year from 79 to 76, but remained significantly higher than 2021’s index number, 70. This year’s decline is unsurprising given where we were in the pandemic and supply chain crises a year ago. After three years, it’s perhaps easy to forget that the earlier stages of the pandemic and lockdowns were not just profoundly disruptive to our businesses but to us all personally. While supply chain and workforce constraints, for example, may be softening, very high levels of disruption persist. When we look at our first survey, which was conducted in the fall of 2020, the index is up substantially (six points) on those levels.

The index scores are a measure of both the magnitude of disruption in the past 12 months, as well as the complexity based on the number and degree of challenges reported by executives.

ALIXPARTNERS DISRUPTION INDEX

Responding to disruption is the greatest strategic challenge for business leaders, and it is unlike the tests they are used to. They must confront an environment that is shaped not just by the magnitude and sheer number of different disruptive forces, but also by their unpredictability and the complexity of their interconnected impact.

The AlixPartners Disruption Index—a measure of the number and intensity of disruptive forces companies face—edged down this year from 79 to 76, but remained significantly higher than 2021’s index number, 70. This year’s decline is unsurprising given where we were in the pandemic and supply chain crises a year ago. After three years, it’s perhaps easy to forget that the earlier stages of the pandemic and lockdowns were not just profoundly disruptive to our businesses but to us all personally. While supply chain and workforce constraints, for example, may be softening, very high levels of disruption persist. When we look at our first survey, which was conducted in the fall of 2020, the index is up substantially (six points) on those levels.

The index scores are a measure of both the magnitude of disruption in the past 12 months, as well as the complexity based on the number and degree of challenges reported by executives.

ALIXPARTNERS DISRUPTION INDEX

No one would say things are calming down. In fact, nearly four out of five CEOs say their businesses have been highly disrupted, an increase of 10 percentage points over last year.

A constant and accelerating bombardment of challenges is their single-biggest worry.

On a regional level, most countries report lower levels of disruption this year. The outlier, though, is Asia, where China reported a 14% increase on the back of resurgent COVID-19 lockdowns and deteriorating economic conditions. Japan also reported a 5% increase year over year. Among industries, energy companies reported higher levels of disruption, on the back of war in Ukraine and price volatility, as did consumer– products companies, which struggled with inflationary pressures and a slowing global economy.

Leadership strategies, business processes, and operating models that worked well in the past break down in the face of disruptive change. Businesses report accelerating the rate of business model change.

An environment like this is dangerous for the complacent and candy for the energetic. In it, the disparities between winners and losers are growing. Profits are progressively more concentrated among a few top firms. For CEOs, the risks of inertia have never been higher, but the opportunities have never been greater to capitalize on change. At a time when CEO turnover is at historic highs and the chief executive role has increased in complexity, 70% of CEOs in our survey worry about losing their jobs due to disruption. While down slightly from 72% last year, this figure is still up significantly on pre-pandemic levels, when 52% reported worrying about losing their jobs.

But smaller companies are more likely to be in reactive mode: The largest companies are 15% more likely to say they drive disruption in their industry.

Despite these concerns, business leaders are optimistic about the future. After three years of the pandemic, supply chain disruptions, and energy shortages, plus inflation at 40-year highs and a war in Europe, perhaps business leaders are becoming more confident in their ability to manage through competing crises while maintaining their focus on the future. Indeed, business leaders are about 12% more optimistic about their own companies than they are about the economy as a whole. The opportunities in the future to unlock greater productivity, make life better for people, protect the environment, and increase international cooperation are tremendous, if we can all rise to the challenge.

No one would say things are calming down. In fact, nearly four out of five CEOs say their businesses have been highly disrupted, an increase of 10 percentage points over last year.

A constant and accelerating bombardment of challenges is their single-biggest worry.

On a regional level, most countries report lower levels of disruption this year. The outlier, though, is Asia, where China reported a 14% increase on the back of resurgent COVID-19 lockdowns and deteriorating economic conditions. Japan also reported a 5% increase year over year. Among industries, energy companies reported higher levels of disruption, on the back of war in Ukraine and price volatility, as did consumer– products companies, which struggled with inflationary pressures and a slowing global economy.

Leadership strategies, business processes, and operating models that worked well in the past break down in the face of disruptive change. Businesses report accelerating the rate of business model change.

An environment like this is dangerous for the complacent and candy for the energetic. In it, the disparities between winners and losers are growing. Profits are progressively more concentrated among a few top firms. For CEOs, the risks of inertia have never been higher, but the opportunities have never been greater to capitalize on change. At a time when CEO turnover is at historic highs and the chief executive role has increased in complexity, 70% of CEOs in our survey worry about losing their jobs due to disruption. While down slightly from 72% last year, this figure is still up significantly on pre-pandemic levels, when 52% reported worrying about losing their jobs.

But smaller companies are more likely to be in reactive mode: The largest companies are 15% more likely to say they drive disruption in their industry.

Despite these concerns, business leaders are optimistic about the future. After three years of the pandemic, supply chain disruptions, and energy shortages, plus inflation at 40-year highs and a war in Europe, perhaps business leaders are becoming more confident in their ability to manage through competing crises while maintaining their focus on the future. Indeed, business leaders are about 12% more optimistic about their own companies than they are about the economy as a whole. The opportunities in the future to unlock greater productivity, make life better for people, protect the environment, and increase international cooperation are tremendous, if we can all rise to the challenge.

WHAT GROWTH LEADERS DO DIFFERENTLY: A BIAS FOR ACTION GIVES SOME COMPANIES AN EDGE

Just under a fifth of respondents to our survey (18%) say that their companies set the pace when it comes to growth in their industry. These are the growth leaders. They are distributed more or less equally among industries–a little less likely than their slower-growing rivals to be in consumer products or retail, and a little more likely to be in financial services or telecommunications.

Growth leaders’ response to disruption differs materially

from others.

First, while growth leaders don’t report higher levels of disruption– 64% compared with 61% for the rest–they are much more likely to say that they drive disruption rather than react to it: 77% compared with 47%. They are also more determined to undertake big, bold change: 57% say they are changing business models this year, compared with 25% of slower-growing companies.

But while they are driving and taking bold steps, they are also less satisfied with how well they and their leadership teams are responding to the challenges they face.

Growth leaders exhibit not only superior

performance, but also show greater determination

to perform even better.

In supply chain, 69% of growth leaders say they are setting the pace in disruption; only 6% of the other companies say they are pacesetters.

In workforce and talent management, 64% of growth leaders say their companies set the pace; only 8% of the other companies say they are pacesetters. By a 92% to 83% margin, growth leaders are more likely to have an enterprise-wide workforce plan that is linked to strategy.

In digital tools and technology, 73% of growth leaders say they are setting the pace versus. 9% for slower-growing companies

Finally, the growth leaders appear to be taking faster, bolder measures to prepare for and respond to the slowing economy. In general, they are more likely to believe that a recession will be short. More than half say they are extremely optimistic about how well their companies will fare in a downturn; they are twice as optimistic as slower growers. Nevertheless, the growth leaders are taking more aggressive steps to protect themselves:

Seven out of ten companies are changing their business models now or within the next year—a response to disruption that is itself disruptive for the companies, employees, and customers affected. Acquisitions, sales, and carveouts are often part of business model change: portfolio adjustments that drive or accompany other initiatives such as digital transformation or dramatic shifts in operating models and costs.

Mann+Hummel Gruppe, a family-owned manufacturer of filtration systems headquartered in southwestern Germany, is one company that has changed its model—in M+H’s case, by exiting its non-filtration businesses in order to deepen and extend its filtration expertise for customers in industries ranging from agriculture and automotive to real estate and waste management. As part of the transformation, AlixPartners helped M+H to divest its high-performance plastic parts business, selling it to Mutares, a German company that specializes in buying companies in special situations.

Deals like this require sharp bifocal vision. First, the company needs to see the strategic big picture for both for itself and for the business it is carving out or spinning off, so that each finds itself in a better position than it was before. Second, it needs the detailed-oriented, close focus to design the operational, back-office, and customer-facing capabilities each will need to compete successfully. Ideally, our experience shows, strategy and execution—M&A Lead Advisory and the PMO—should be led by the same team, to ensure that both views stay in focus.

In the case of M+H, that process included optimizing the plastics business for sale, developing the target operating model with separation of key so-called Zebra plants, and contract manufacturing agreements, conducting a competitive M&A process including marketing, due diligence and negotiations, and more—all the while ensuring that both filtration and plastics businesses stayed up and running well during the process. The best management teams, after all, harness the forces of disruption to work for them, not against them.

Seven out of ten companies are changing their business models now or within the next year—a response to disruption that is itself disruptive for the companies, employees, and customers affected. Acquisitions, sales, and carveouts are often part of business model change: portfolio adjustments that drive or accompany other initiatives such as digital transformation or dramatic shifts in operating models and costs.

Mann+Hummel Gruppe, a family-owned manufacturer of filtration systems headquartered in southwestern Germany, is one company that has changed its model—in M+H’s case, by exiting its non-filtration businesses in order to deepen and extend its filtration expertise for customers in industries ranging from agriculture and automotive to real estate and waste management. As part of the transformation, AlixPartners helped M+H to divest its high-performance plastic parts business, selling it to Mutares, a German company that specializes in buying companies in special situations.

Deals like this require sharp bifocal vision. First, the company needs to see the strategic big picture for both for itself and for the business it is carving out or spinning off, so that each finds itself in a better position than it was before. Second, it needs the detailed-oriented, close focus to design the operational, back-office, and customer-facing capabilities each will need to compete successfully. Ideally, our experience shows, strategy and execution—M&A Lead Advisory and the PMO—should be led by the same team, to ensure that both views stay in focus.

In the case of M+H, that process included optimizing the plastics business for sale, developing the target operating model with separation of key so-called Zebra plants, and contract manufacturing agreements, conducting a competitive M&A process including marketing, due diligence and negotiations, and more—all the while ensuring that both filtration and plastics businesses stayed up and running well during the process. The best management teams, after all, harness the forces of disruption to work for them, not against them.

DEEPENING DISRUPTIONS

DISRUPTION DISCUSSIONS

In this video series, AlixPartners CEO Simon Freakley, Co-head of Asia & Americas Lisa Donahue, Head of EMEA Rob Hornby, and Head of Industries David Garfield discuss key themes from the 2023 AlixPartners Disruption Index and the actionable steps growth leaders are taking to thrive in the age of disruption.

Every executive team performs a balancing act

between short- and long-term thinking, delivering this year’s earnings while investing for growth and eliminating waste while also innovating in products, services, and processes. It also needs to find the right mix of direction and empowerment, using the power of centralization versus releasing the energy of decentralization.

That is tricky even in a placid business environment, and 2023 promises to be anything but placid. Companies face an extraordinary confluence of forces seemingly bent on knocking them off balance. Their expense budgets have been shoved sideways by inflation. Their revenue forecasts have been blown apart by softening demand and, for some, recession. Rising interest rates are playing havoc with financing, acquisitions, and other plans. A soaring dollar is messing with costs and revenues. The economic uncertainty is compounded by political uncertainty in Asia, Europe, and North America. And plans can be upended by continuing and unpredictable aftershocks from COVID-19.

More than ever, leaders need the ability to focus tightly on short-term issues while simultaneously envisioning their long-term strategy. A critical part of that bifocal capability is understanding what the major disruptive forces are, which will affect their company most, and what the effect on industry dynamics is likely to be in both the short and long run. The forces we have described in this report play out differently depending on the company and its competitive context. Is a disruptor something to work through–a challenge or an opportunity, but not a transformative one? Will it reshuffle the deck, producing new winners and losers? Will it change the game entirely, fundamentally altering the structure or profitability of an industry?

BECOME RECESSION READY.

Planning as usual won’t suffice for unusual times. A budget and a plan that extrapolate from last year are likely to prove irrelevant; they might even be dangerous. Instead, companies should build five interlocking capabilities for recession readiness:

Most companies see danger too late. Indeed, 87% of executives say they feel optimistic (including 31% extremely optimistic) about the future of their business considering a pending recession. Smart companies will take off the rose-colored glasses and deploy early warning systems that produce better visibility into financial flows and identify signals of potential distress across all levels of business (e.g. business units, geographies, channels and even individual products). Executives at these levels are likely to be the first to spot slowing orders, growing inventory, or delayed collections–but they often miss the broader significance of what they see. Redesign planning and your monthly and quarterly reviews so anyone running a business unit sees and reports all three views of your business: the P&L, balance sheet, and cash flow.

Input costs, raw materials, labor, and transportation–all may be much more volatile than usual. A zero-based cost budget provides much more specific information about sources of cost vulnerability; it is a powerful weapon against disruption. The same is true on the revenue side. Most plans look more keenly at costs than at revenue, but sudden drops in demand occur in a recessionary environment. What would that do? What assets will be impacted? Which customers, products, and channels are most profitable? Which are most vulnerable?

When times are tough, cash is king. Working capital initiatives need to be built into company plans, with specific targets for how much will be saved when and by whom. Those plans—and the resulting cash generation—need to be actively monitored. This is the moment to hold onto cash and further build reserves by drawing down lines of credit, and to reexamine balance sheets and business models to identify fixed costs–such as fleets of trucks and server farms–that can be turned into variable costs via outsourcing.

Scenario planning is a powerful recession-readiness tool. What would a mild, moderate, and severe recession do to your business? Which specific parts of the business would be hurt first? Which would be hurt most? What are the early warning signs that will inspire action? Who on your team is best equipped for what might lie ahead? Prepare three scenarios: An easy-to-do set of actions that will conserve cash with no long-term damage, such as hiring and travel freezes; a lever to pull if a downturn is fairly steep or long, with actions like delaying new product launches or cutting capital spending; and a crisis playbook in case of deep trouble. Prepare these scenarios now, when you don’t need them. That way, if business goes south, the question becomes when to act, not what to do.

Recession proofing cannot stop at the company door. Supply-chain disruptions have faded in the headlines, but not in the executive suite: 52% of business leaders say supply chain disruption is more of a challenge for their company than it was a year ago. The combination of recession and inflation changes the challenge. Before, it was firefighting, as companies scrambled to find supply at whatever cost and wherever they could. Now they should renegotiate the prices they just agreed to, so as not to overpay for goods they might not sell. They should build the same kind of early-warning system they should have for internal operations: control towers that provide real-time information about availability, price, and supplier performance, because a recession might put some suppliers in trouble, particularly smaller tier-two and tier-three companies they might not know well. Margin management must return to a front-and-center position among supply chain capabilities. This requires developing the ability to measure profitability at a granular level and integrate data in real time.

BECOME RECESSION READY.

Planning as usual won’t suffice for unusual times. A budget and a plan that extrapolate from last year are likely to prove irrelevant; they might even be dangerous. Instead, companies should build five interlocking capabilities for recession readiness:

Tune up financial warning systems.

Most companies see danger too late. Indeed, 87% of executives say they feel optimistic (including 31% extremely optimistic) about the future of their business considering a pending recession. Smart companies will take off the rose-colored glasses and deploy early warning systems that produce better visibility into financial flows and identify signals of potential distress across all levels of business (e.g. business units, geographies, channels and even individual products). Executives at these levels are likely to be the first to spot slowing orders, growing inventory, or delayed collections–but they often miss the broader significance of what they see. Redesign planning and your monthly and quarterly reviews so anyone running a business unit sees and reports all three views of your business: the P&L, balance sheet, and cash flow.

Understand costs and revenues at a deep level of detail.

Input costs, raw materials, labor, and transportation–all may be much more volatile than usual. A zero-based cost budget provides much more specific information about sources of cost vulnerability; it is a powerful weapon against disruption. The same is true on the revenue side. Most plans look more keenly at costs than at revenue, but sudden drops in demand occur in a recessionary environment. What would that do? What assets will be impacted? Which customers, products, and channels are most profitable? Which are most vulnerable?

Maximize cash generation.

When times are tough, cash is king. Working capital initiatives need to be built into company plans, with specific targets for how much will be saved when and by whom. Those plans—and the resulting cash generation—need to be actively monitored. This is the moment to hold onto cash and further build reserves by drawing down lines of credit, and to reexamine balance sheets and business models to identify fixed costs–such as fleets of trucks and server farms–that can be turned into variable costs via outsourcing.

Pre-plan for action.

Scenario planning is a powerful recession-readiness tool. What would a mild, moderate, and severe recession do to your business? Which specific parts of the business would be hurt first? Which would be hurt most? What are the early warning signs that will inspire action? Who on your team is best equipped for what might lie ahead? Prepare three scenarios: An easy-to-do set of actions that will conserve cash with no long-term damage, such as hiring and travel freezes; a lever to pull if a downturn is fairly steep or long, with actions like delaying new product launches or cutting capital spending; and a crisis playbook in case of deep trouble. Prepare these scenarios now, when you don’t need them. That way, if business goes south, the question becomes when to act, not what to do.

Improve supply chain cost, flexibility, and resilience.

Recession proofing cannot stop at the company door. Supply-chain disruptions have faded in the headlines, but not in the executive suite: 52% of business leaders say supply chain disruption is more of a challenge for their company than it was a year ago. The combination of recession and inflation changes the challenge. Before, it was firefighting, as companies scrambled to find supply at whatever cost and wherever they could. Now they should renegotiate the prices they just agreed to, so as not to overpay for goods they might not sell. They should build the same kind of early-warning system they should have for internal operations: control towers that provide real-time information about availability, price, and supplier performance, because a recession might put some suppliers in trouble, particularly smaller tier-two and tier-three companies they might not know well. Margin management must return to a front-and-center position among supply chain capabilities. This requires developing the ability to measure profitability at a granular level and integrate data in real time.

POSITION FOR NEAR-TERM OPPORTUNITIES

One company’s retreat is another company’s chance to advance–if it’s alert and ready to act. Opportunistic acquisitions and aggressive digitalization are particularly attractive.

A buyer’s market.

Companies with cash, strong balance sheets, and strategic foresight can take advantage of the distress of others. What are the actions you would take to reshape your market, if you could? If you plan ahead of time, you will be faster to act when opportunities become available. When it comes to acquisitions, the best positioned buyers will be those with cash, strong balance sheets, strategic foresight, and superior operational capabilities. Rising interest rates may sideline some financial buyers, creating opportunities for those who can buy with less leverage. Operational due diligence–looking deeply into the plants, processes, and products of target companies–may become more important than financial engineering. Companies with that combination of financial flexibility and operational chops can put themselves in a strong position to accelerate when the economy turns back up.

Cost-focused digitalization.

Investments and initiatives that give digital capabilities industrial strength deliver big benefits in both the short- and long-term. Executives are three-and-a-half times more likely to struggle with the execution of their technology plans than with finding the budget for them. Many digital initiatives, such as predictive maintenance and production and back-office automation, throw off significant savings while also transforming how business is done. Similar opportunities exist in speeding up moves to cloud computing, digital payments, and workforce management. Many companies invested heavily in digitalization to support hybrid work during the pandemic; now three out of 10 executives say that integration of those systems should be a top priority for their IT and operations teams.

A buyer’s market.

Companies with cash, strong balance sheets, and strategic foresight can take advantage of the distress of others. What are the actions you would take to reshape your market, if you could? If you plan ahead of time, you will be faster to act when opportunities become available. When it comes to acquisitions, the best positioned buyers will be those with cash, strong balance sheets, strategic foresight, and superior operational capabilities. Rising interest rates may sideline some financial buyers, creating opportunities for those who can buy with less leverage. Operational due diligence–looking deeply into the plants, processes, and products of target companies–may become more important than financial engineering. Companies with that combination of financial flexibility and operational chops can put themselves in a strong position to accelerate when the economy turns back up.

Cost-focused digitalization.

Investments and initiatives that give digital capabilities industrial strength deliver big benefits in both the short- and long-term. Executives are three-and-a-half times more likely to struggle with the execution of their technology plans than with finding the budget for them. Many digital initiatives, such as predictive maintenance and production and back-office automation, throw off significant savings while also transforming how business is done. Similar opportunities exist in speeding up moves to cloud computing, digital payments, and workforce management. Many companies invested heavily in digitalization to support hybrid work during the pandemic; now three out of 10 executives say that integration of those systems should be a top priority for their IT and operations teams.

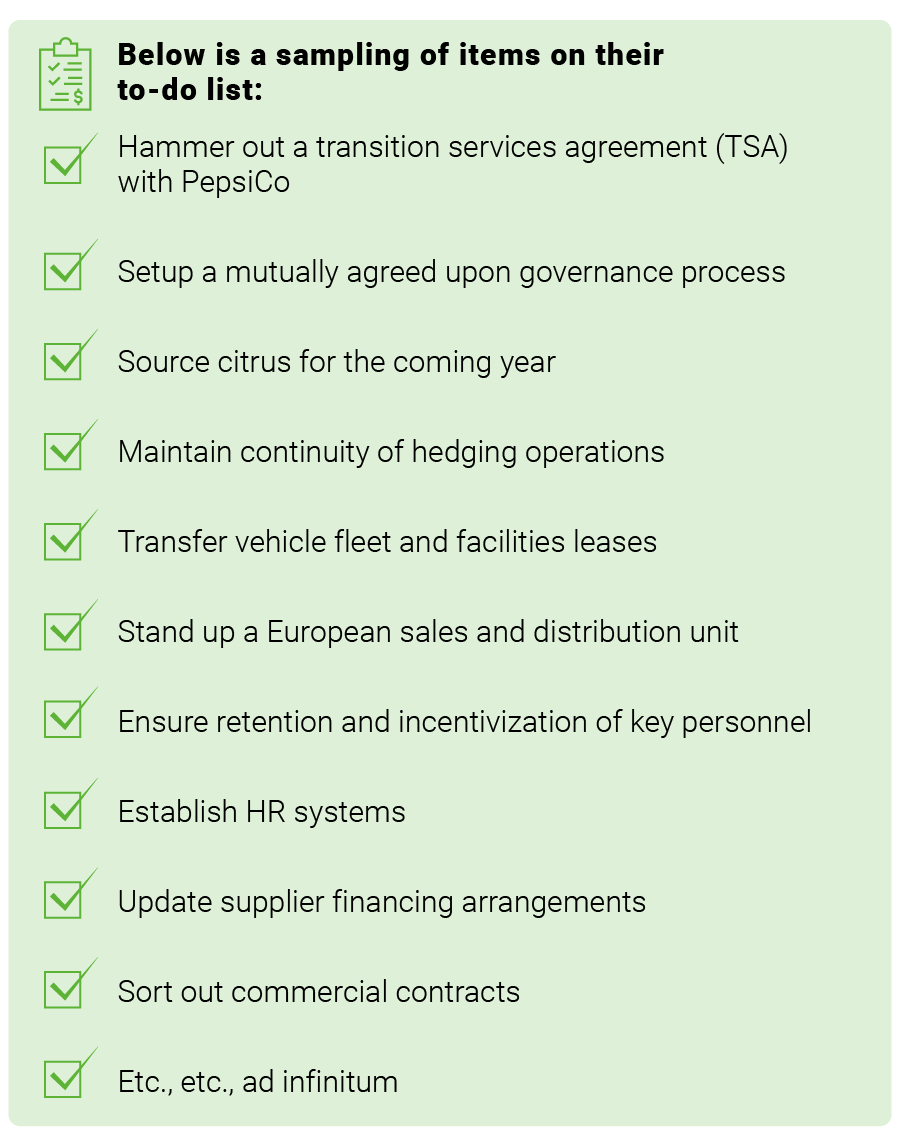

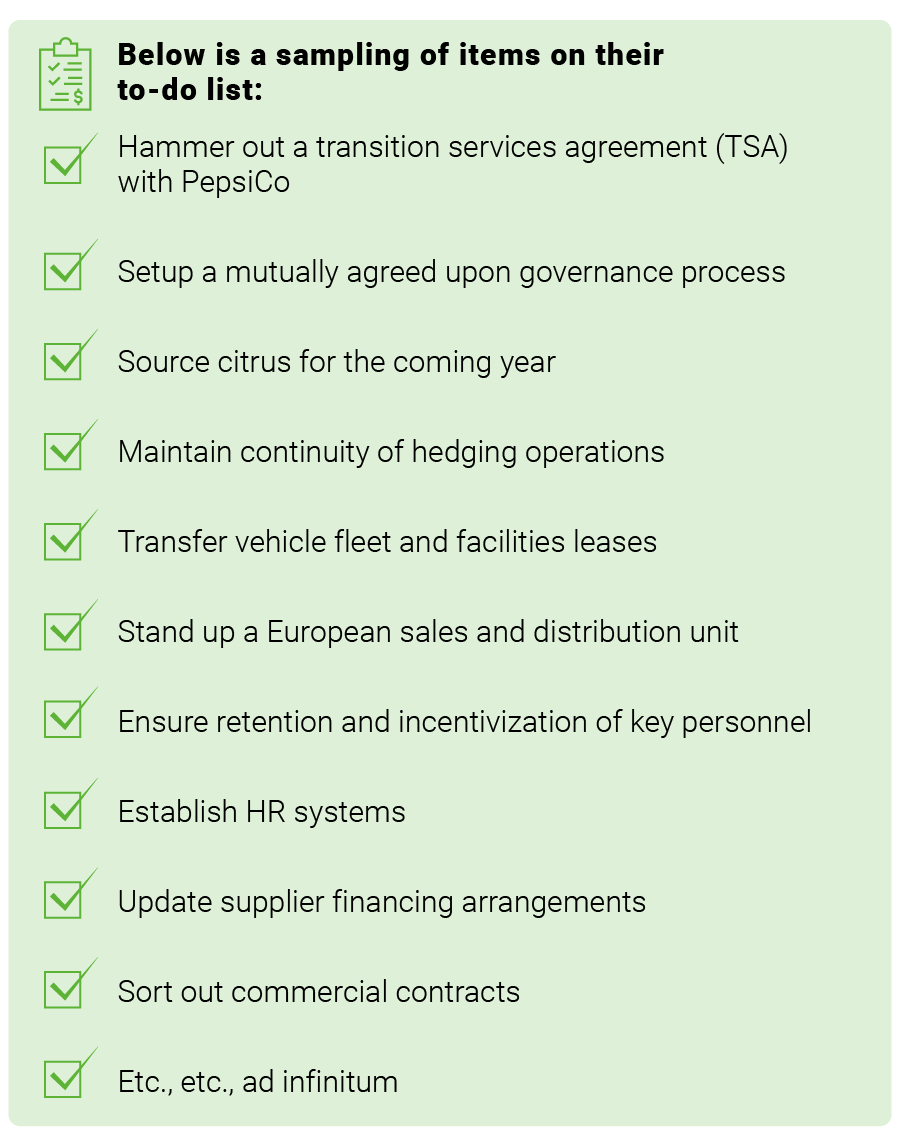

So much to do. So little time to get it all done.

Tropicana Brands Group faced a crunch as it considered the fast-approaching closing date for its carve-out from corporate parent PepsiCo. The incoming sponsor, PAI Partners, a Paris-based private equity firm and one of the largest in Europe, was intent on enabling the new business—an array of category-leading beverage brands including Tropicana, Naked and Dole juices and Tazo and Pure Leaf bottled teas—to emerge from the transaction on Day One as a fully operational independent company with $3 billion in annual revenue.

It was a heavy lift. Under PepsiCo’s ownership, the teams responsible for the various brands had little interaction with one another, and each brand was deeply enmeshed with the parent’s functions and departments, from IT to Legal and from R&D to Supply Chain. To rewire all those connections and create a freestanding organization, PAI and Tropicana Brands had to advance along several fronts simultaneously. Below is a sampling of items on their to-do list:

A tall order for any organization—much less one with a mere 86 business days to complete the job, all while keeping their global enterprise running day-to-day.

Tropicana’s successful sprint to the line was supported by a team of advisors that crossed practice and geographical boundaries and encompassed a wide range of skills, expertise and experience. It was vital to stand up a state-of-the-art project management office as rapidly as possible to categorize tasks, assign priorities and accountabilities, and monitor progress. It was equally vital to begin to instill a new identity and purpose in the people of Tropicana Brands to focus and energize their work. The identity: empowered advocates for Tropicana Brands Group. The purpose: to create a cohesive new business from a disparate assortment of brands. In 86 business days.

The new mindset helped drive the organization to address more than 30 multi-disciplinary priorities with minimum disruption to day-to-day business. By the time the deal closed, Tropicana Brands had identified $100 million to $150 million in EBITDA improvements. It exited several sections of its TSA with PepsiCo more than three months early, for a savings of $25 million. Additionally, the new business learned to operate as a global unit, a big change from the prior disparate siloed model. And from day one, Tropicana Brands was poised for present success and future growth.

LONG TERM: ACCELERATED VALUE CREATION

The purpose of business is to create value for investors, employees, customers, and communities. Depending on circumstances, a leadership team might prioritize identifying sources of value and competitive advantage, protecting value against risks like data breaches, fraud, and compliance, strengthening value creation in established and new markets, or restoring value where it has been damaged or destroyed. In disruptive times, it is important to be clear about these priorities, then pursue them in an aggressive, accelerated way. Speed to value is inherently good, but it is especially important because macro trends have a way of becoming suddenly urgent as ecosystems reach their tipping points. Change happens slowly, then all at once.

By a nearly two-to-one margin, executives will prioritize organic growth over inorganic growth (M&A and partnerships). Consumer products and telecommunication companies are the most acquisitive industries, but they too put most weight on organic growth. While deals will and should still happen, both strategically and opportunistically, they need to be firmly grounded in a strong ongoing business. M&A gets riskier as rising interest rates add to an acquirer’s burden; forecasted positive synergies from deals have a way of evaporating under the hot sun of a tough economy. The smartest growth initiatives–organic or inorganic–are likely to be those closest to a company’s core business, where they can leverage existing economies of skill and scale.

There’s never a downside to efficiency, but the upside is even greater when growth is hard to come by. Operations teams should base their plans on economic profit–that is accounting for the cost of capital–calculated by customer, product, and plant. This approach not only increases margins, but can also profoundly improve working capital management. That increases enterprise value in and of itself, but also fuels growth, because the cheapest capital in the world is money you can free up from funding day-to-day operations.

Abrupt changes in consumption patterns, spending behavior, digital adoption, and workplace practices are rendering longtime customer-care strategies obsolete.

Mapping customer journeys reveals two especially valuable customer-value–creating programs. First are those that make customer journeys easier, quicker, and friction-free. Becoming “easy to do business with” saves time and money for both parties; it also reduces customer churn and increases customer lifetime value–things are doubly valuable in a downturn, when new customers are scarce.

The second category covers investments in customer success, that is, ensuring that customers themselves are getting the most out of what they have bought. The concept of customer success emerged in technology industries (particularly enterprise software), where progressive sellers dispatched experts to help customers use their complex products more fully. Unlike customer service, which fixes problems, customer success focuses on surfacing opportunities for customers.

The full value of digital transformation comes when cost-oriented programs (see above) are paired with customer-oriented investments. Studies by AlixPartners and the MIT Center for Information Systems Research show that these “future-ready” digital companies enjoy profit margins 9.4% points higher than companies where digital operations are scattershot and transactional.

The extraordinary tightness in labor markets has loosened. Today, 50% say that attracting and retaining skilled workers will become easier in the year ahead (while just 23% say this will become harder). But the long-term transformational issues remain.

Executives see problems with productivity in remote and hybrid work. Nine out of 10 CEOs (90%) say employees working in the office are more productive than employees working from home or remotely. Four out of five (82%) say the pace of change is making employee skills rapidly obsolete. They also say that new employees entering the workforce do not have the skillset necessary to succeed at their company (81%), and that shifts in employee values and preferences are driving disruption within their company (82%). That includes the set of social and values issues that fall under the ESG (environmental, social, governance) label; three out of four CEOs (75%) say they feel pressure to take a stance on societal issues to avoid backlash from employees or team members.

Clearly the employee value proposition needs to change. Traditional HR tools, including compensation, training, and retention programs, can do only so much. They need to work in tandem with advanced thinking about AI, automation, work redesign, and business model transformation in a comprehensive, cross-functional program to maximize the return on human capital. Today, less than a quarter of the total market value of large companies can be explained by their physical and financial assets. The productivity of human capital–and intangible assets generally–needs attention across the C-suite

and the board.

BE PREPARED TO ACT

In any given market, in any given period, some companies overperform and some underperform. During 2008, the worst year for U.S. stock market performance so far this century, the S&P 500 fell more than 38%1, but Dollar Tree returned 61%, Vertex Pharmaceuticals 31%, and H&R Block 26%2. In 2021, the Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 19%, but the stocks of Home Depot and Microsoft both jumped more than 50%, while Verizon fell by 11% and Walt Disney by 14%3.

Averages don’t dictate performance. Leaders and their choices do: when and where to invest, where and when to pull back. Averages are at best a way to gauge how well they played their hands. The same disruptive forces that knock one company back can propel another ahead. Ford’s stock nearly quadrupled the same year both General Motors and Chrysler declared bankruptcy.

BE PREPARED TO ACT

In any given market, in any given period, some companies overperform and some underperform. During 2008, the worst year for U.S. stock market performance so far this century, the S&P 500 fell more than 38%1, but Dollar Tree returned 61%, Vertex Pharmaceuticals 31%, and H&R Block 26%2. In 2021, the Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 19%, but the stocks of Home Depot and Microsoft both jumped more than 50%, while Verizon fell by 11% and Walt Disney by 14%3.

Averages don’t dictate performance. Leaders and their choices do: when and where to invest, where and when to pull back. Averages are at best a way to gauge how well they played their hands. The same disruptive forces that knock one company back can propel another ahead. Ford’s stock nearly quadrupled the same year both General Motors and Chrysler declared bankruptcy.

In a complex, fast-changing time, leaders need detailed and informative data about the performance of their enterprises: the profitability of their assets, the productivity of their people, their efficiency and innovativeness, their cash, and their competitive advantage. They need to be able to see all of these, both holistically and in detail. At the same time, they need to be monitoring the environment, watching the competitors they know, staying alert for rivals unforeseen and looking for disruptions that might be brief, like thunderstorms, or long-lasting, like shifts in tectonic plates. Like captains on a ship, they need to watch the dials in the engine room at the same time as they scan the sea.

And they need to act. It’s no use having bifocal vision–pixels and big picture–without a plan to react to threats and an appetite to exploit opportunities, however big or small they are. The most successful companies we studied this year were not clustered in one industry or one geography. They all faced the same disruptive forces, just as rain falls on the just and unjust alike. No, what sets the leaders apart is their ability to see what’s happening in a clear, unbiased way; to see what really matters, and then to act.

In a complex, fast-changing time, leaders need detailed and informative data about the performance of their enterprises: the profitability of their assets, the productivity of their people, their efficiency and innovativeness, their cash, and their competitive advantage. They need to be able to see all of these, both holistically and in detail. At the same time, they need to be monitoring the environment, watching the competitors they know, staying alert for rivals unforeseen and looking for disruptions that might be brief, like thunderstorms, or long-lasting, like shifts in tectonic plates. Like captains on a ship, they need to watch the dials in the engine room at the same time as they scan the sea.

And they need to act. It’s no use having bifocal vision–pixels and big picture–without a plan to react to threats and an appetite to exploit opportunities, however big or small they are. The most successful companies we studied this year were not clustered in one industry or one geography. They all faced the same disruptive forces, just as rain falls on the just and unjust alike. No, what sets the leaders apart is their ability to see what’s happening in a clear, unbiased way; to see what really matters, and then to act.

The world keeps getting more complex, and industries around the globe are feeling the impact of disruption in disparate ways. Where responding to disruption is the greatest strategic challenge for business leaders, companies’ growth expectations are going to continue to be challenged well into 2023.