The disruptive impact of climate change works in two directions. One is the transition to a green economy. As energy production shifts from fossil fuels to renewable energy, companies revamp operations to reach goals of Net Zero carbon neutrality, government policies, and regulations change, and a so-called circular economy emerges where waste is eliminated or recycled.

The other transition is adapting to, and sometimes suffering from, the effects of climate change. As the number and scale of calamitous weather events increases, sea levels rise, and some regions become less productive or habitable. The more business and society can mitigate climate change through a transition to a green economy, the less they will have to adapt to it; and the more they can mitigate and adapt, the less they will suffer.

The war in Ukraine underscored the global economy’s continuing need for fossil fuels, but it has also accelerated the transition to renewables. For the first time, the International Energy Agency believes that the role of fossil fuels in total energy supplies has passed its peak.1 Even in China, coal and oil use will decline by the end of the decade thanks to huge investments in renewable energy and other alternative energy sources and technologies.

At the same time, most wealthy nations have successfully

decoupled economic growth from carbon emissions, meaning that they are able to increase GDP while reducing their carbon footprint not just as a percentage of GDP but in absolute terms–even accounting for the carbon content of imports and exports. It remains a question of when–or even if–emerging economies can make that transition2.

The transition dramatically changes the amount and flow of energy investment. Already today, global clean energy investments, which total $1.5 trillion a year, are 50% larger than investments in fossil-fuel–based energy. Wind and solar accounted for 76% of new generation capacity in the U.S. in 2021. The shift to renewables has been fueled by price and accelerated by policy. The cost of generating offshore and onshore wind power is expected to decline between 37% and 49% by 2050.3 Solar power costs show a similar trend.

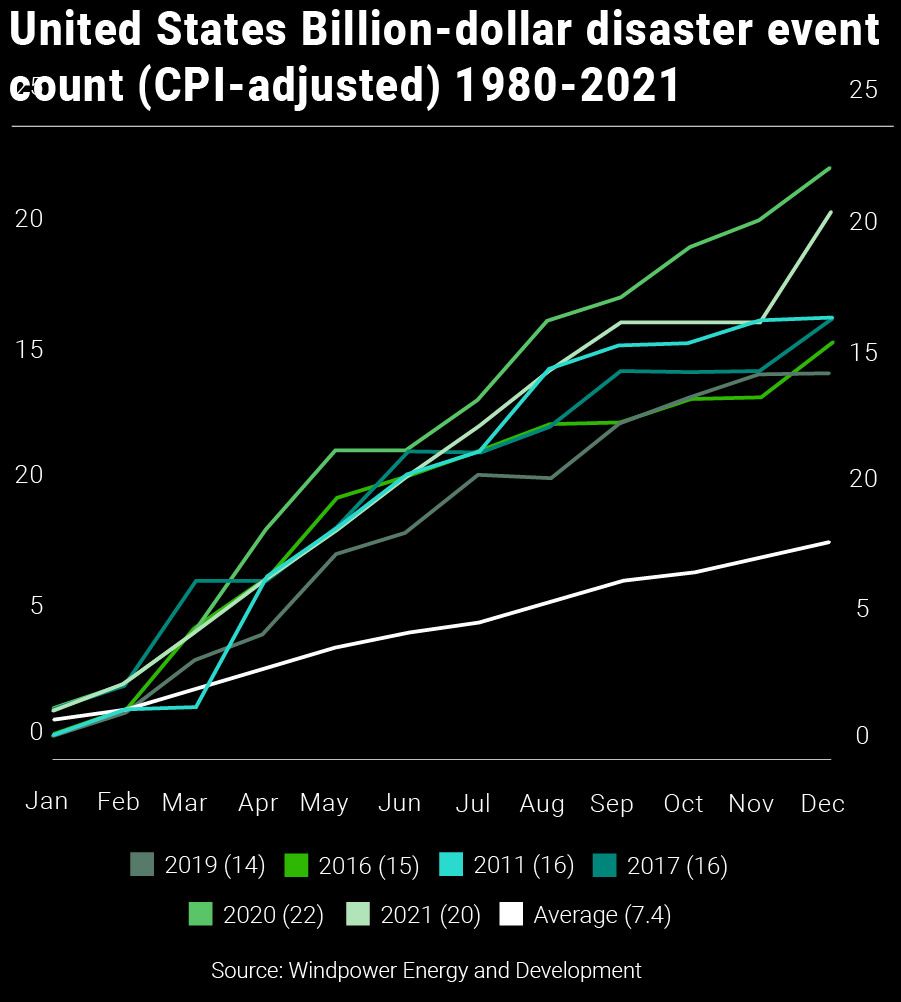

While industry makes the switch to renewables, companies and citizens must also cope with the costs and risks of climate change itself. Calamitous floods in Pakistan and Nigeria, droughts in Africa and the American West, more and more powerful storms–all these increase risk and cost, endanger existing investments and will reshape or disrupt business plans in both the short- and long-term. Since 2000, droughts have increased in frequency and duration by a third, according to United Nations data. In the U.S., billion-dollar weather disasters are occurring more than twice as often now as they have on average since 1980. The insurance industry is, of course, on the hook for some of the direct cost of catastrophe, but climate change affects business planning and decisions for everything, from aerospace and agribusiness to transportation and utilities.

The war in Ukraine underscored the global economy’s continuing need for fossil fuels, but it has also accelerated the transition to renewables. For the first time, the International Energy Agency believes that the role of fossil fuels in total energy supplies has passed its peak.1 Even in China, coal and oil use will decline by the end of the decade thanks to huge investments in renewable energy and other alternative energy sources and technologies.

At the same time, most wealthy nations have successfully

decoupled economic growth from carbon emissions, meaning that they are able to increase GDP while reducing their carbon footprint not just as a percentage of GDP but in absolute terms–even accounting for the carbon content of imports and exports. It remains a question of when–or even if–emerging economies can make that transition2.

The transition dramatically changes the amount and flow of energy investment. Already today, global clean energy investments, which total $1.5 trillion a year, are 50% larger than investments in fossil-fuel–based energy. Wind and solar accounted for 76% of new generation capacity in the U.S. in 2021. The shift to renewables has been fueled by price and accelerated by policy. The cost of generating offshore and onshore wind power is expected to decline between 37% and 49% by 2050.3 Solar power costs show a similar trend.

While industry makes the switch to renewables, companies and citizens must also cope with the costs and risks of climate change itself. Calamitous floods in Pakistan and Nigeria, droughts in Africa and the American West, more and more powerful storms–all these increase risk and cost, endanger existing investments and will reshape or disrupt business plans in both the short- and long-term. Since 2000, droughts have increased in frequency and duration by a third, according to United Nations data. In the U.S., billion-dollar weather disasters are occurring more than twice as often now as they have on average since 1980. The insurance industry is, of course, on the hook for some of the direct cost of catastrophe, but climate change affects business planning and decisions for everything, from aerospace and agribusiness to transportation and utilities.

Climate change and its effects are not only reshaping our environment but also destroying lives, shifting populations, and remaking industries.

The proliferation of wildfires is but one example. More than half4of the acres burned each year in the western United States are directly linked to climate change. The number of dry, warm, and windy days—perfect wildfire weather—in California has more than doubled5 since the 1980s.

For northern and central California utility PG&E, a series of intense wildfire seasons, culminating in the 2018 Camp Fire, resulted in the widespread destruction of property, a number of fatalities, and a severe impact on the lives of thousands of affected Californians. PG&E equipment was implicated as a contributing factor to a number of the wildfires, giving rise to tens of billions of dollars in asserted liabilities, ultimately driving the need for PG&E to seek bankruptcy protection in early 2019.

For a company meeting the energy needs of over 16 million people, ceasing operations was not an option. PG&E would have to skillfully navigate the restructuring process and find the resources to compensate victims and invest to reduce wildfire risk, while continuing to serve its customers.

Over an 18-month period, that coincided with pandemic lockdowns, the company, advised by AlixPartners, successfully executed a $59 billion restructuring, that included $13.5 billion in payments to a trust to compensate wildfire victims. As one of the most complex bankruptcies in U.S. history, this financial restructuring was only the beginning. Dramatic operational transformation was also necessary, but the company’s emergence from Chapter 11 helped set PG&E on course for a safer and more reliable future.

CLIMATE TRANSITION AND INDUSTRY DISRUPTION

The climate transition occupies an ever-more-prominent place on the agendas of senior executives and boards of directors, with the fastest-growing companies taking a more proactive stance than their slower-growing competitors. Two years ago, just over a quarter (27%) of executives said that environmental and social issues had a very or extremely significant impact on their enterprises. Today, just under a half (45%) say they are experiencing a major impact as they address disruptions from environmental and social change.

Nowhere is the disruptive impact of climate transition more evident than in the automotive industry. Sales of fully electric and hybrid vehicles doubled between 2020 and 2021; sales of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) are growing twice as fast as sales of hybrids. By 2035, the EU will ban sales of internal combustion engines (ICEs); the U.K. will do the same by 2030, while China, the world’s biggest car market, expects 40% of new vehicles sold there to be electric by 2030. By that time, thanks to incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, 52% of U.S. vehicle sales will be electric, hybrid, or fuel-cell powered–a greater than tenfold increase from 2021.6

Adding it all up, AlixPartners expects battery electric vehicles (BEVs) to be the dominant automotive platform worldwide by 2035.

The transition will not be cheap: Automakers and suppliers are poised to spend more than a half-trillion dollars funding this shift through 2026 alone. The change will upend the entire automotive industry ecosystem. The raw materials and parts used to make battery electric vehicles cost more than twice as much as the inputs for internal combustion engines, largely due to the cost of lithium and other battery components. The transition to battery power for vehicles will by itself cause an 8.1% increase in global demand for copper.7

While many vehicle components will be unaffected by the transition (like seats, axles, and steering mechanisms), the production of drive trains, sensors, and of course batteries themselves will be altered or require new processes, with huge disruptive effects. Only about 28% of BEV powertrain spending is likely to be accessible by the industry’s current supply base. The remaining 72% will be captured by newcomers or by the automobile companies themselves, which plan to insource much of what they used to buy.

CLIMATE TRANSITION AND INDUSTRY DISRUPTION

The climate transition occupies an ever-more-prominent place on the agendas of senior executives and boards of directors, with the fastest-growing companies taking a more proactive stance than their slower-growing competitors. Two years ago, just over a quarter (27%) of executives said that environmental and social issues had a very or extremely significant impact on their enterprises. Today, just under a half (45%) say they are experiencing a major impact as they address disruptions from environmental and social change.

Nowhere is the disruptive impact of climate transition more evident than in the automotive industry. Sales of fully electric and hybrid vehicles doubled between 2020 and 2021; sales of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) are growing twice as fast as sales of hybrids. By 2035, the EU will ban sales of internal combustion engines (ICEs); the U.K. will do the same by 2030, while China, the world’s biggest car market, expects 40% of new vehicles sold there to be electric by 2030. By that time, thanks to incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, 52% of U.S. vehicle sales will be electric, hybrid, or fuel-cell powered–a greater than tenfold increase from 2021.6

Adding it all up, AlixPartners expects battery electric vehicles (BEVs) to be the dominant automotive platform worldwide by 2035.

The transition will not be cheap: Automakers and suppliers are poised to spend more than a half-trillion dollars funding this shift through 2026 alone. The change will upend the entire automotive industry ecosystem. The raw materials and parts used to make battery electric vehicles cost more than twice as much as the inputs for internal combustion engines, largely due to the cost of lithium and other battery components. The transition to battery power for vehicles will by itself cause an 8.1% increase in global demand for copper.7

While many vehicle components will be unaffected by the transition (like seats, axles, and steering mechanisms), the production of drive trains, sensors, and of course batteries themselves will be altered or require new processes, with huge disruptive effects. Only about 28% of BEV powertrain spending is likely to be accessible by the industry’s current supply base. The remaining 72% will be captured by newcomers or by the automobile companies themselves, which plan to insource much of what they used to buy.

In a big shift partly caused by the transition to BEVs, industry profit pools are flowing from the supply base (59% of economic profits in 2018) and the original equipment manufacturers (OEMs; 63% of profits in 2023).

The disruptive effects will be equally dramatic downstream as gas stations give way to (or transition into) charging stations and face new competition from charging stations in private homes, apartment complexes, public parking facilities, and retailers and shopping malls. The number of public charging stations has entered the “hockey stick” phase of growth,8 , aided by federal grants. Ohio alone, for example, will distribute $100 million over five years to fund rapid charging stations on major highways crisscrossing the state.9

The value of the public vehicle charging market is forecast to grow at a compound annual rate of nearly 37%, which means that it will double every two years. By 2030, the U.S. will need $48 billion dollars to fund the growth of its charging infrastructure, only $11 billion of which has already been committed.

Downstream changes won’t stop with charging, of course. Repair, maintenance and replacement parts–the entire automotive aftermarket, a business with half a trillion

dollars in annual revenue in the U.S. alone–are all up for grabs. Mechanics will do different work. Some parts and jobs, like mufflers and oil changes, will fade away entirely. The mechanics will need new skills, too, and their old nickname, ‘grease monkeys’, will have to go.

BACK TO THE FINDINGS REPORT

AlixPartners Disruption Index 2023

The world keeps getting more complex. Myriad disruptions arise, feed off one another, and cascade around the world at an accelerated pace. The leadership challenge is unprecedented: Amid so many formidable issues—daunting long-term disruptions and difficult short-term demands—how should we focus our all-too-finite resources of capital and time? As leaders focus on rising to the challenge of disruption, AlixPartners believes leaders who seize its opportunities will be positioned for success. View the findings report, here.